I love that I can read Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Pushkin in their original language. You really get to understand the spirit of the Russian soul, which the West often misunderstands. Fyodor Tyutchev, a Russian poet and diplomat, perfectly articulated this idea of the soul of a nation in his 1866 poem:

Умом Россию не понять,

Аршином общим не измерить:

У ней особенная стать –

В Россию можно только верить.

Which translates to something like this. It doesn’t do it justice, but here it is:

You cannot grasp Russia through reason,

Nor measure her by common standards.

She possesses a nature all her own—

In Russian, one can only believe.

…and this nature is in me. Russian identity is in me; it seeped in during seventy years of Soviet rule. This is not something I will ever fully shake off or reason myself out of.

It is part of who I am as a human being.

Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian Nobel Prize laureate, in her remarkable biography, Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, examines the legacy of the Soviet Union by describing this very identity, a type of person shaped by decades of Marxist ideology and Soviet life, the “Soviet man.”

She writes, “Communism had an insane plan: to remake the ‘old breed of man,’ ancient Adam. And it really worked…Perhaps it was communism’s only achievement. Seventy-plus years in the Marxist-Leninist laboratory gave rise to a new man: Homo sovieticus.”

But here is the problem: Homo sovieticus is not a nationality or an ethnicity. It is not even a culture. It’s an ideology that erased my true identity, an identity that is Persian, ancient, written in my DNA.

I am Tajik. And before the Soviets told us we were something separate, something new, we were Persian.

Locating Tajikistan

Most Americans have never heard of Tajikistan. When I say I’m Tajik, most people have no clue what it means.

Every time I tell people where I’m from, I have to emphasize its geographical location by naming countries they have heard of on the news. I often mention Afghanistan, so it clicks. That’s when they go, “Oh, I see.” I know if I say Afghanistan, I can expect a reaction — raised eyebrows, suspicious look, crossed arms (the universal signs of distrust), and a nervous smile to ensure they are not being too obvious.

Having lived in the States for a long time, their distrust is understandable. I don’t blame people. I get it. I watch the news too.

And then, after I mention the most unstable country in Central Asia, I get even more controversial: I say we share a border with China. And to top it off, I explain how we share a common history with Communist Russia, which joined all 15 republics into the Soviet Union.

My background sounds like a neo-conservative’s worst nightmare, but there is really nothing I can do about it. I did not choose it. If I had a choice, I would have chosen to be born as a white man here in the United States in the ‘70. It was the best time to be in America. Houses cost $40, food was not a luxury, starting a family was expected, and the healthcare system didn’t give people anxiety.

I’m not going to lie, after a while, explaining to people where I’m from gets exhausting, but I take it upon myself to educate people and offer them a perspective they might not been taught.

This is how you break the cycle of dehumanization.

This is how you teach Americans that communism is not a very good idea.

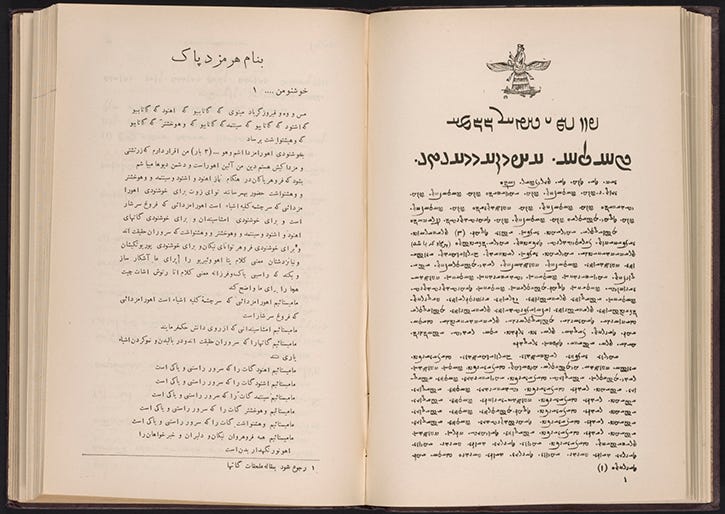

Sometimes I wonder if people realize that when they read Rumi, one of the best-selling poets in America, they are reading a poet who wrote in my language. In Persian. In the script, my great-grandfather could read, and I can’t.

Rumi was not Turkish (though Turkey claims him. Nice try, but no). He wasn’t Arab. He was Persian. He was from Wakhsh, which is present-day Tajikistan. He was an Ismaili mystic. In Ismaili Islam, his writings are considered spiritually sacred. As a former Muslim, now a Christian, any time I read Rumi and his expression of love for the Divine, I can’t help but see the similarities between my devotion to Christ and Rumi’s deep affection for the Almighty. It’s almost as if Rumi were a Christian. He understood that divine, cosmic mystic love — the relationship between the Creator and his creation. When Rumi describes his intoxication with the Divine, that is exactly how I feel about Jesus.

But more on that in future posts.

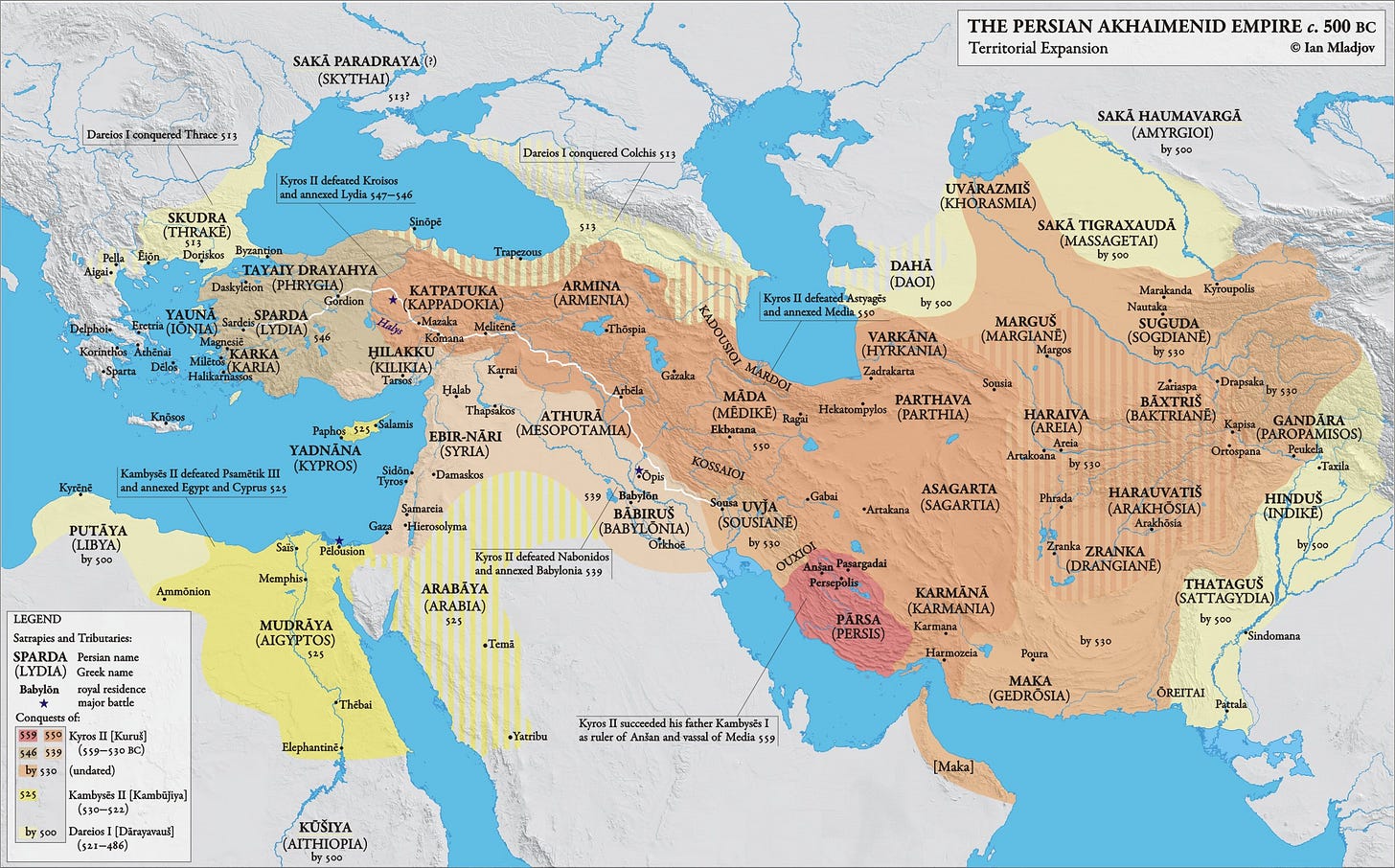

Going back to the Persian identity. Tajiks are ethnically Persian. We speak a dialect of Farsi. Our poetry Hafez, Ferdowsi, Saadi, the same poets, Iranians and Afghans claim. We are not Turkic. We are not Slavic. We are Persian, part of a cultural and linguistic heritage that stretches back thousands of years.

I was born into a Pamiri family, an Eastern Iranian ethnic group considered one of the world’s oldest people groups. In Pamiri homes, the ceiling is constructed with five levels, representing the five elements of Zoroastrianism: earth, water, fire, air, and light. At the center, there is always an opening for smoke, the chorkhona, a sacred space where fire burned continuously.

Walk into any house in the Pamirs today, and you will see this architecture. We build our homes as temples, and somehow they survive.

If you travel to the Pamir Mountains and enter any house, you will hear languages that don’t sound like standard Persian but share the same ancient roots. For centuries, we survived invasions — Turkic, Mongol, and Islamic. Our identity bent but never broke. We preserved our language, our poetry, our fire temples, our way of life.

Years before my father passed away from cancer, I asked him a question about our Pamiri identity. I will never forget when he told me that the reason the Pamiri people are so resilient despite everything we have been through is that we have lived in the harsh mountain climate for thousands of years. He said that living in the mountains makes you tough, and this toughness is passed down genetically.

He was right. It does.

For centuries, we fought the invaders. For centuries, our resilience helped us survive.

And then came the Soviets.

The Day We Forgot How To Read Our Own Names

When the Soviet Union carved up Central Asia in the 1920s and 1930s, it was’t random. Stalin deliberately divided Persian-speaking peoples to prevent pan-Persian unity that could threaten Soviet control. Tajikistan was created as a separate republic, cut off from Iran and Afghanistan, and our Persian identity was systematically dismantled.

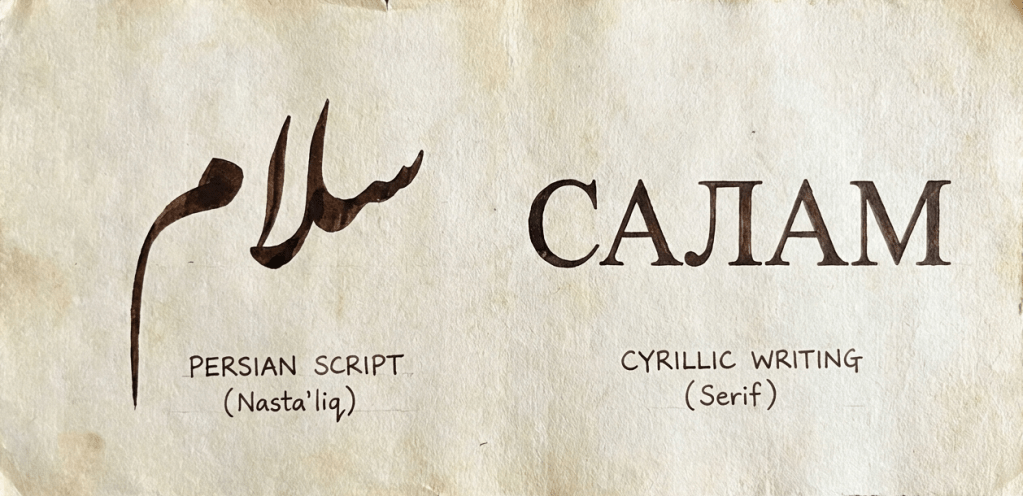

They changed the alphabet.

Imagine you wake up one day, and the alphabet you have used your entire life is suddenly illegal. The beautiful, graceful curves of Persian script, the same script that wrote the Shahname, the Persian Book of Kings, were replaced with harsh, boring, and ugly-looking Cyrillic blocks.

Within ten years of the Soviet alphabet change, literacy in Persian script dropped from 95% to nearly 0%. Before 1929, Tajiks used the Persian script. By 1940, an entire generation couldn’t read their parent’s letters.

They renamed our cities. Historical Persian names were replaced with Russian or Soviet names. Our maps were rewritten. Our geography became Soviet, not Persian. Take a look at cities like Samarkand and Bukhara. These were Persian cities, the center of learning and poetry. These cities are part of our heritage and history. Today they are in Uzbekistan, a country invented by the soviets. To this day, people in Samarkand and Bukhara identify as Tajik (Persian), despite holding Uzbek nationality.

They also rewrote our textbooks, including our history. Historically, Persian names were replaced with Russian or Soviet names. For example, growing up, all of my aunts and uncles had second names — they were Russian names.

I don’t know the full history behind this, but for some reason, it was deemed necessary. Considering how the Soviets conditioned us to view our own culture and heritage as secondary, it makes sense that people felt compelled to adopt second names to fit in and assume a new identity — one that was not only mandatory but also clearly preferred. Even my mother, whose real name is Bakhtibegim, would go by Klara (Clair), which is a common Russian name. My father never liked it. He believed that your name determined your destiny. He used to tell her, “ Your real name means a woman of great destiny, but you go by Klara, which means nothing.” She would mostly ignore it because fitting in and sounding Russian was cooler than being a woman of “great destiny.”

Sounding Russian became more culturally superior. We were taught that our salvation came from Moscow, not from the poets and empires that came before.

We slowly began to forget who we were.

The Soviet “Tajik”

The Soviet Union promoted a new identity: “Tajik.”

Not Persian. Not Iranian. Tajik, an ethnicity, was designed to make us forget who we actually were. We were told we were different from Iranians, separate from Afghans, despite speaking the same language and sharing the same blood.

Before the Soviets took over, Tajik children memorized 60,000 verses of the Persian epic, Shahname, by Ferdowsi. After the Soviet Union took over, kids had to recite Lenin’s speech, and Shahname was presented as “Tajik folklore,” severed from its Persian context, and our cultural identity tied to it.

Every city in Tajikistan had a statue of Lenin in its main square, a constant reminder of where our allegiance belonged. Growing up, I thought this was normal; it wasn’t until I moved to the United States that I realized how bizarre it actually is. Can you imagine traveling from city to city in the United States and seeing a bronze statue of Donald Trump everywhere? Me neither.

The Soviets called our language “Tajik,” and we are the only Persian-speaking people on earth who can’t read our own historical texts without learning a foreign alphabet. They didn’t just erase our alphabet; they also created a huge divide between us and the rest of the Persian-speaking world.

We are Persians who were taught to forget we are Persian.

Russian holidays were added to our calendars, food to our menus, films to our movie theaters, and music to our radio stations. Our identities began to enmesh. And if you know what this term means in psychology, you know how long it takes to undo its damage.

I’m still partially enmeshed with my Sovieticus.

Three Languages, Three Identities

I grew up speaking Russian with friends at school because I attended a Russian school. Again, Russian schools were preferred over Tajik ones because they were considered far more prestigious and offered greater opportunities. I spoke Tajik with friends and Pamiri with family at home.

Each language unlocked a different identity within me and forced me to act accordingly. Speaking Russian, attending a Russian school, and wearing Western clothing existed alongside speaking Tajik with friends and wearing traditional Tajik dress — two parallel realities I inhabited simultaneously. Those identities were at war with each other: one shaming the other for being uneducated, the other condemning it as immodest and shameful.

At home, in my Pamiri household, Ismaili Islam shaped my worldview. We were different from the rest of the Tajiks. We had our own language, our own form of Islam, and our own customs and traditions. Even within the small Tajik population, there is tremendous diversity. And even within the tiny Pamiri community, that diversity expands from neighborhood to neighborhood. We are so small and yet so diverse.

Religion was suppressed because communism replaced it. Marxism, Leninism, and Stalinism became our imposed religions. Zoroastrianism, the ancient Persian faith, had already been eradicated by Islam at that point. The Pamiri people are the only ones who preserved elements of Zoroastrianism. Islam itself was driven underground, its spiritual heritage dismissed as backward and incompatible with Soviet atheism.

We learned to live in layers. Soviet on the surface. Persian underneath. And we all knew not to speak too loudly about the underneath.

The loss wasn’t just political — it was existential.

A generation grew up not knowing they were Persian. They read Russian classics but couldn’t access their own. They learned Soviet history but not the history of the Samanid Empire, the first Persian state after the Islamic conquest, which had its capital in what is now Tajikistan. We lost connection to our linguistic siblings in Iran and Afghanistan.

And perhaps most tragically, we internalized the Sovient narrative. We began to believe that we were something lesser, a small, backwards republic dependent on Moscow for survival, when our land is filled with natural resources.

We forgot we were heirs to one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

Living In-Between Two Identities

I am Homo sovietucis, even though I was born right when the system collapsed. I can’t deny it. Russian is in my bones. I think in Russian metaphors. I carry Soviet education, Soviet work ethic, Soviet cynicism.

But I am also Persian. And the tragedy is that these two identities don’t coexist peacefully; one was designed to erase the other.

To this day, I hear Russians express disdain that Tajiks no longer speak Russian fluently. “We gave you education, infrastructure, literacy,” they say. “And now you abandon our language?”

Why are we still expected to learn or speak Russian in our own country? It was left in shambles after the collapse, and we had to rebuild it from scratch. We had to rebuild after a brutal civil war and the years of trauma that it caused. And no, Russia did not give us literacy. We were literate when they were still peasants.

Russian was never our language. It was imposed. And when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, we finally had the chance to reclaim what was ours. Yet even now, more than thirty years after independence, we struggle. Cyrillic is still our official script. Russian is still widely spoken despite the criticism that we receive for not remaining “sovietucis.” Today, more than 1 million Tajiks work in Russia as migrant laborers, still dependent on the empire that “freed” us. The damage runs deep.

And the racism persists. Tajiks in Russia are treated as second-class laborers, even though we helped rebuild their khruschevkas into high-rise buildings. We fought in their wars and shared their Union for seventy years. We helped build Moscow. We provide cheap labor. And yet we are still seen as less human.

Where did we go wrong? What was the point of unity if, in the end, we were never seen as equals?

Does Homo sovieticus mean your worth is determined only by Marxist ideology, not by your ethnicity, your language, your skin, your ancient heritage?

The answer is no. No ideology has the power to define our worth.

We Are Still Here

Today, a new generation of Tajiks is remembering.

We are learning Persian script again. We are reading Rumi and Hafez in the alphabet our ancestors used. We are reconnecting with our Persian siblings, realizing we share more than the Soviets wanted us to know. We are teaching our children that they are not just Tajik. They are Persian. They are inheritors of an empire that once stretched from the Mediterranean to India. They are the children of poets, astronomers, and philosophers.

The Soviet Union tried to erase us. It almost worked. But cultural identity can be buried; it cannot be destroyed.

In 2026, cultural heritage battles continue across the Persian world. The Taliban banned Persian New Year celebrations in parts of Afghanistan. Iran’s government uses Persian identity as political propaganda. And in Tajikistan, the authoritarian president exploits Persian heritage when it’s convenient while suppressing genuine cultural revival.

The irony is bitter: after fighting for decades to remember we are Persian, we now have to fight to reclaim it from the people who want to control what “Persian” means.

Cultural identity isn’t just remembering — it’s deciding who gets to tell the story.

I will always carry the Soviet inside me. I will always read Tolstoy and feel something stir. I still get excited every time I discover a new Russian grocery store in my NYC neighborhood. That’s the paradox of Homo sovieticus: we are composites, stitched together.

But underneath the Russian vernacular, underneath the Cyrillic alphabet and the Soviet education, there is something older, something that refused to die.

So, you live in that in-between space.

You are too foreign for home. Too foreign for here. Never enough for both.

I am Tajik. I am Pamiri Tajik. And no deaology, no matter how insane its ambitions, could fully erase that.

What happens when an empire erases your identity, but you survive anyway? Do you mourn what was lost? Do you celebrate what remains? Or do you do both, holding grief and pride in the same breath?

Because that’s what it means to be Tajik. To be Persian in exile from our own heritage. To be Soviet ghosts haunting Persian bones.

We are the children of erasure, but we are still here.