“Tax Churches”

You will see this comment at the top of the comment section, loaded with likes, on almost any viral post about church scandals, ministry abuse, or shady 501(c)3 practices.

The anger is understandable.When churches and Christian organizations exploit tax-exempt status while leadership lives lavishly, or when ministries harm the vulnerable they claim to serve, the outrage is justified.

I have spent most of my career working for Christian organizations, and most of my Christian walk volunteering for various churches and ministries. After years of experience I have a clear understanding of what is actually happening within these organization. While there are many Christian non-profits that do meaningful work and have a significant, positive impact on people’s lives, there is also a troubling reality in how a substantial number of them are structured and managed.

The challenges facing many Christian non-profits and churches today go far beyond a handful of high-profile megachurch leaders in Rick Owens skinny jeans and Jordan 1 Retro High sneakers. The underlying issues are often systematic, rooted in organizational structure, internal culture, financial stewardship, and the theological beliefs that shape how these institutions operate.

Why Are Christian Non-Profits Problematic?

1. The Tyranny of Donor Loyalty

Christian non-profits draw from a complex web of funding sources that shapes their priorities and incentives. Individual donors provide the backbone through monthly recurring gifts, one-time donations, major gifts from high-net-worth supporters, and planned giving through wills and estates. Churches contribute through partnerships, denominational support, mission offerings, and funding for church plants. Institutional money flows in from private foundations, donor-advised funds, and Christian foundation networks.

Many organizations also pursue government contracts and grants from federal agencies, state and local governments, and faith-based initiative programs for services like childcare, adoption, and refugee resettlement. Earned revenue is generated through product sales, conference registrations, membership dues, consulting services, and licensing agreements. Special events like fundraising galas, golf tournaments, auctions, fundraising running, and benefit concerts generate additional income. Digital fundraising, email campaigns, text-to-give, and even cryptocurrency donations has exploded in recent years.

Mission trips and project-specific campaigns allow supporters to fund specific causes like child sponsorship or well-building projects. Some mature organizations benefit from endowment income, investment returns, and rental property revenue. Finally, in-kind donations of goods, services, volunteer labor, and pro-bono professional work round out the funding picture. This funding diversity sounds healthy in theory but in practice, it creates competing loyalties and incentive structures that pull organizations away from their state missions.

Hedge fund managers often create nonprofit foundations for both strategic and philanthropic reasons. Large donations provide substantial tax benefits, such as immediate deductions and the ability to avoid capital gains taxes by giving appreciated assets, making the real cost of giving much lower. Foundations also let donors contribute a large sum of money upfront, claim the full tax break, and distribute grants gradually, since they are required to give away only about 5% of assets annually. The remaining funds can be invested, grow, and support long-term influence while also helping families build a lasting charitable legacy. Beyond financial incentives, foundations allow donors to support causes they value which improve their public image, and build influential relationships.

While some criticize them as tax shelters, most view them as a mix of practical planning and genuine philanthropic intent. However, the issue begins to arise when the donor’s altruistic intent directly contradicts the Gospel. That’s when things get complicated and eventually the conflict of interests lead to spiritual and moral corruption.

Christian non-profits often operate with an unspoken priority: keep donors happy at all costs. This creates a perverse incentive structure where organizational decisions are filtered through one question: “Will this upset our supporters?”

The result is predictable. Ministries become risk averse, unwilling to address controversial issues or serve certain marginalized groups if it might alienate their donor base. For example: an international relief organization might stay silent on systematic injustice because its wealthy donors prefer charity over advocacy. Mission drift doesn’t always mean abandoning your original purposes, sometimes it means choosing donor retention over prophetic witness.

This loyalty trap extends beyond just programming decisions. Staff salaries are kept artificially low under the guise “of doing it for the Lord” while executive compensation packages grow.

Marketing budgets balloon to maintain donor engagement while program effectiveness receives less scrutiny. The organization exists not primarily to serve its stated beneficiaries but to maintain the donor ecosystem that funds it.

We brand our work with Christ’s name, yet we often neglect to follow His leading. When donor expectations drive our choices, Christ ends up on the sidelines of the very mission that bears His name. We use His name in vain, betray Him for far less than thirty shekels, and drive the nails into the cross over and over again.

2. Financial Stewardship

When you receive money that you did not earn, stewarding that money well becomes hard. It is in the human nature to take for granted things that have been handed to them for free. Christian organizations love to showcase their financial accountability. They display Charity Navigator ratings, undergo annual audits, and emphasize how much of every dollar goes “directly to ministry.” But financial stewardship in many Christian non-profits has become performative rather than substantive.

The metrics we use to evaluate Christian organizations are often deeply flawed. High program-to-overhead ratios sound virtuous but can mask organizational dysfunction. Underpaid staff, deferred maintenance, inadequate training, no human resources, and non-existent professional development all make the numbers look better while undermining actual effectiveness. Meanwhile, executive leadership positions multiply, more VPs, more directors, more “strategic” roles that distance decision-makers from actual work.

Real stewardship asks harder questions: Are we actually accomplishing our mission? Are there more effective ways to achieve our goals? Should we even exist, or would these resources do more good elsewhere? But these questions threaten organizational survival, so they are rarely asked honestly.

The 501(c)3 structure itself can enable this dysfunction.Tax-exempt status provides a competitive advantage that allows inefficient or ineffective organizations to persist. Without market pressures or genuine accountability to the communities they serve, Christian non-profits can coast on donor goodwill and emotional appeals rather than demonstrated impact.

This is not the Kingdom’s way of stewarding blessings well!

3. Compartmentalizing Ministry vs. the Christian Life

Perhaps the deepest and main problem in the Christian non-profit world is how we have professionalized and compartmentalized what should be the natural overflow of Christian community.

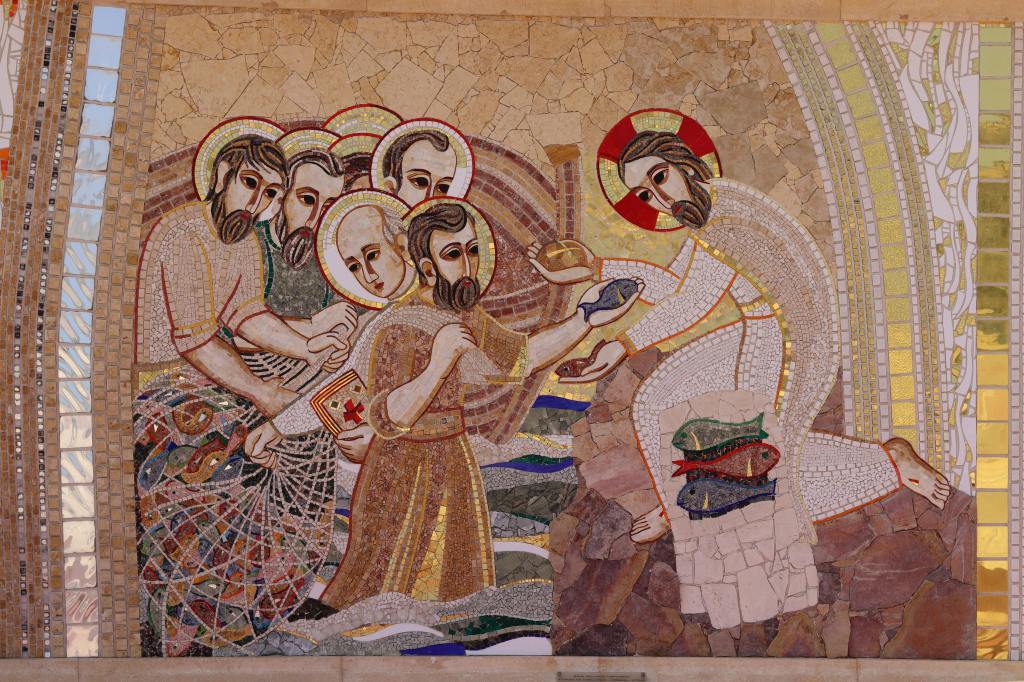

Early Christians didn’t have non-profit organizations. They had churches, communities of believers who shared resources, served the vulnerable, and bore witness of the resurrection. When they saw someone is need, they met it. When they encountered injustice, they spoke against it. Ministry wasn’t a specialized function outsources to organizations; it was how Christians lived.

Modern Christian non-profit allow us to outsource discipleship. Instead of personally caring for the widow, we donate to a ministry that does it. Rather than welcoming the stranger, we fund or refund refugee resettlement programs. We write checks instead of washing feet. This isn’t inherently wrong, specialization and scale can multiply impact, but it has allowed many Christians to substitute financial support for actual obedience.

The professionalization on ministry has also created a clergy/laity divide in new forms. “Ministry” becomes something done by paid staff at Christian organizations, not the calling of every believer in their daily life. We have create a class of professional Christians whose job is to do the work of the kingdom while everyone else funds it.

Christianity is a way of life. We are called “the people of the way” for a reason. When you give your life to Christ, you gain a new identity, an identity that fundamentally reorients how you relate to money, power, community, and service.

The problem with many Christian non-profits isn’t that they exist but they have become substitutes for genuine Christian community and discipleship. They allow us to feel like we are participating in God’s work without the messiness of actual relationship, sacrifice, and transformation.

This doesn’t mean all Christian organizations are corrupt or that we should abandon institutional ministry. Many do remarkable, faithful work. But it does mean we need to ask harder questions: Does this organization serve its stated mission or its own perpetuation? Does it empower local communities or create dependency? Does it call us toward deeper discipleship or allow us to outsource our calling?

Perhaps most importantly: Are we using Christian non-profits to supplement faithful Christian living, or replace it?

The answer to “tax churches” isn’t simply better financial accountability, though we desperately need that. The answer is recovering the vision of Christianity where the church itself, the gathered community of believers, is the primary vehicle for God’s mission in the world. Where every Christian understands their work, their neighborhood, and their relationship as the arena for kingdom service. Where organizations exist to equip and amplify what Christians are already doing in their daily lives, not to do it for them.

Until we reclaim that vision, Christian non-profits will continue to struggle with the same systematic problems: serving donors over beneficiaries, optimizing metrics over missions, and professionalizing what should be the shared work of the entire body of Christ.

Leave a comment